“I was born for a storm and a calm does not suit me.”

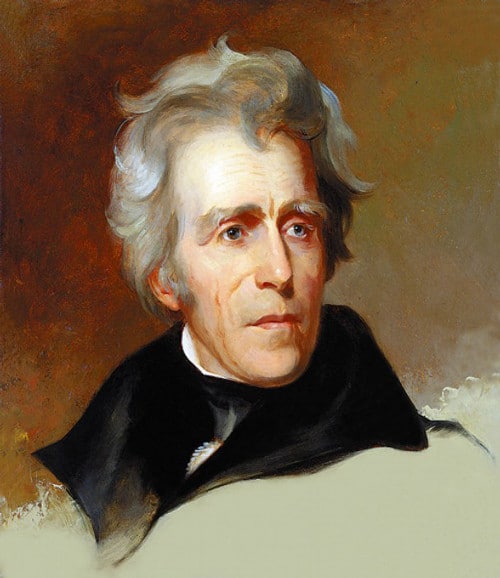

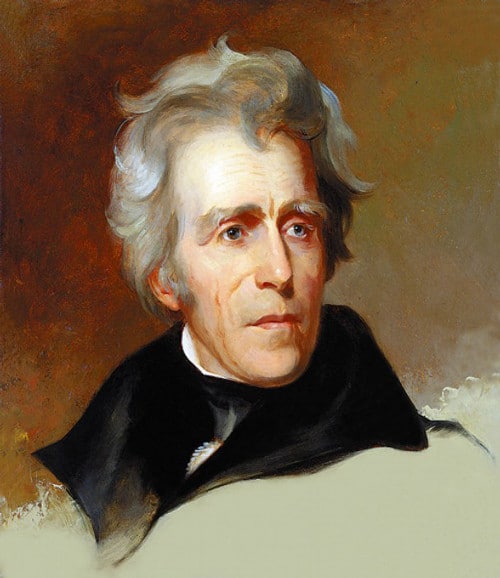

While his countenance graces our $20 bill, many Americans do not know much about the life of Andrew Jackson. He is often remembered as the hero of the Battle of New Orleans or condemned as the man responsible for the Trail of Tears. He was in truth a man of many contradictions: impetuous and reckless frontiersman and charming gentleman; enforcer of the Indian Removal Act and devoted father of an adopted Indian orphan; champion of freedom and the preservation of the Union and unrepentant slave holder. He was described as both a quintessential man’s man, “fond of well-cut clothes, racehorses, dueling, newspapers, gambling, whiskey, coffee, a pipe, pretty women, children, and good company,” and a gentleman with a soft side: “there was more of the woman in his nature than in that of any man I ever knew — more of a woman’s tenderness toward children, and sympathy with them.”

He was the first president to come from the common people and break the Virginia aristocracy’s hold on that office. After his inauguration, he threw open the doors of the White House for a public reception; the crowd of drunken well-wishers who attended grew so huge and unruly they had to be lured back out with large tubs of spiked punch placed on the front lawn. He was the first president to see himself as the direct representative of the people and thus to believe that his office should have great power and authority in shaping national affairs.

There is much to find repugnant in Andrew Jackson’s life and career as it pertains to slavery and Native Americans. But that a man is flawed in some ways does not mean he cannot be inspiring in others, and it would be a shame not to learn from the high points of the life of “The Old Lion”:

Don’t Let Your Circumstances Determine Your Fate

Andrew Jackson’s life story could have been torn straight from a Horatio Alger novel. Jackson’s father died just 2 months before he was born. His mother could not keep the family farm going herself and moved in with her sister. So began a life of dependency for young Andrew. His aunt put his mother to work like a housekeeper, and the boy was always keenly aware of his inferior place in the household. Growing up without a father, he developed a propensity towards anger, recklessness, and defensiveness.

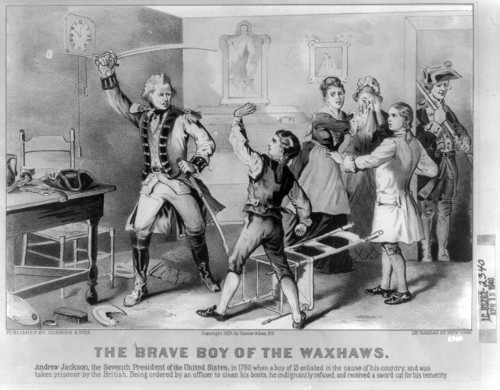

Yet Jackson’s troubles had just begun. The Revolutionary War would grant the country independence, but exact a heavy price on this future president. Hugh, his 16-year-old brother who had gone off to fight, became the first casualty, dying of heat exhaustion at the Battle of Stono Ferry. Andrew, who at age 13 had joined a local militia to serve as a courier, was then captured by British soldiers and imprisoned along with his other brother, Robert. Jackson’s mother successfully pled for the boys to be released, but Robert, who had contracted smallpox while in jail, died two days later. Andrew was also sick, but his mother, assured he was doing well, decided to travel to Charleston to tend to prisoners of war who had become stricken with cholera. Jackson would never see her again; she soon fell ill and passed away. Andrew Jackson, only 14 years old, was now an orphan.

Jackson now had no immediate family and only a few years of education. He lived with a series of relatives, chafed at feeling like an inferior houseguest, squandered an inheritance from his grandfather, and sowed his wild oats. His relatives feared he would become a great embarrassment to his family. He described his situation during this time as “homeless and friendless.”

Jackson felt deeply adrift, but his mother’s last advice to him before she departed for Charleston kept returning to his mind, urging him to turn things around and live a proper and successful life:

“Andrew, if I should not see you again, I wish you to remember and treasure up some things I have already said to you: in this world you will have to make your own way. To do that you must have friends. You can make friends by being honest, and you can keep them by being steadfast. You must keep in mind that friends worth having will in the long run expect as much from you as they give to you. To forget an obligation or be ungrateful for a kindness is a base crime — not merely a fault or a sin, but an actual crime. Men guilty of it sooner or later must suffer the penalty. In personal conduct be always polite but never obsequious. None will respect you more than you respect yourself. Avoid quarrels as long as you can without yielding to imposition. But sustain your manhood always. Never bring a suit in law for assault and battery or for defamation. The law affords no remedy for such outrages that can satisfy the feelings of a true man. Never wound the feelings of others. Never brook wanton outrage upon your own feelings. If you ever have to vindicate your feelings or defend your honor, do it calmly. If angry at first, wait until your wrath cools before you proceed.”

Desiring to honor the memory of his mother, Jackson tried to get back on track and decided to study and apprentice to become a lawyer. He was still living a rowdy life at that point –“I was a raw lad then, but I did my best,” Jackson would later recall — but he began to mark out a path for himself.

He was able to gain admittance to the bar but could not find any clients to represent; he had no clout or experience. So he leveraged the one quality that would help carry him all the way to the White House: his magnetic bearing and charisma. It was a time where connection to great and prosperous families was essential to success, and Jackson used his charm to insinuate himself into these families’ good graces. He was never considered attractive, but his gentlemanly manners, steely, attentive blue eyes, and ability to converse with and warmly engage with people from all walks of life drew others to him. While his rowdy reputation would often precede him, Jackson would instantly disarm those he met and absolutely confound their expectations.

Jackson made the right connections, worked hard, and moved up in the world. With vast stores of personal strength, self-confidence, and perseverance as his only resources, he set out to make a name for himself. His biographer, Jon Meacham, details his astonishing and unexpected rise: “An uneducated boy from the Carolina backwoods, the son of Scots-Irish immigrants…became a practicing lawyer, a public prosecutor, a US attorney, a delegate to the founding Tennessee Constitutional Convention, a US Congressman, a US Senator, a judge of the state Superior Court, and a major general, first of the state militia and then of the US Army.” And then, of course, he would reach the very top of the ladder – attaining the highest office in the land.

Instead of letting adversity break him, Andrew Jackson gathered a gritty strength from his experiences that would enable him to make it through all the tests and trials of his life.

Cultivate Your Leadership

Before he became a politician, Jackson was a great and storied war hero. He was the kind of leader that men would gladly follow to the ends of the earth. Having grown up without a father, Jackson sought to be a father to the men under his command. He treated his men as sons, and in so doing, won their undying loyalty.

When the war with Britain began in the winter of 1812-13, Major General Jackson gathered together 2,000 volunteers and marched them from Tennessee towards New Orleans in anticipation of action. The men had picked up and left behind their professions and families — their entire lives, really — in hopes of being of service to the country. But after journeying for 500 cold miles and reaching Mississippi, the Secretary of War ordered them to disband and return. Jackson refused to leave his volunteers adrift and force the men to find their own way back home. He promised to keep them together, and even use his own money to furnish the supplies necessary for the return trip.

Many of the men had by then fallen ill and could not make the long journey unaided. Yet there were only 11 wagons for the 150 sick men. The regiment’s doctor, Samuel Hogg, asked Jackson what he should do with the sick. “To do sir? You are not to leave a man on the ground.” “But the wagons are full and they will convey not more than half,” Hogg countered. “Then let some of the troops dismount, and the officers must give up their horses to the sick. Not a man, sir, must be left behind,” Jackson declared. The general set the example by immediately turning over his own horses. He walked alongside his men all the way back to Tennessee. By the time the weary troops arrived in Nashville, the men had taken to calling their tender but tough leader “Old Hickory,” a tree whose wood is described thusly: “Very hard, stiff, dense, and shock resistant. There are woods that are stronger than hickory and woods that are harder, but the combination of strength, toughness, hardness, and stiffness found in hickory wood is not found in any other.”

Prize Your Honor and the Honor of Your Loved Ones

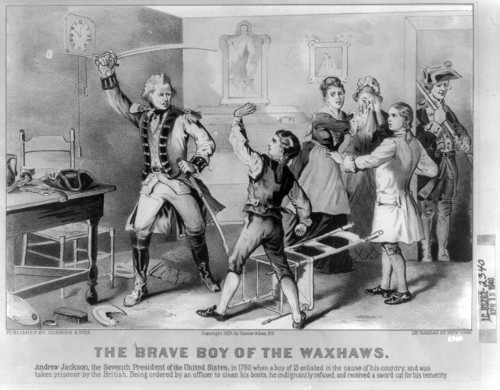

One’s honor was a central occupation of all men during this period, but starting from a young age, Andrew Jackson took it even more seriously than most. During the Revolutionary War, when he and his brother were captured by the red coats, a British officer ordered Jackson to polish his boots. The nervy boy refused, declaring, “Sir, I am a prisoner of war and claim to be treated as such.” Enraged, the officer swung his sword at Jackson. Though he tried to block the blow, it left a scar on his hand and a dent in his head.

Jackson was also ferocious in his desire to protect the honor and well-being of his loved ones. The orphan drew his extended family to him and greatly valued their loyalty. Above all, he valued the bond and honor of his wife of 40 years, Rachel. Because their marriage began under a cloud of controversy (Rachel was not yet divorced when their relationship began), she was subject to attack from Jackson’s political opponents. To Jackson, the slanderer was “worse than a murderer. The murderer only takes the life of the parent and leaves his character as a goodly heritage to his children, whilst the slanderer takes away his good reputation and leaves him a living monument to his children’s disgrace.” Defaming his wife was, as a contemporary recalled, “like sinning against the Holy Ghost: unpardonable.” Biographer James Parton claimed that Jackson “kept pistols in perfect condition for thirty-seven years” to use whenever someone “dared breathe her name except in honor.”

They were dueling pistols. For a southern gentleman of this time, dueling was the honorable way to resolve quarrels and insults. Jackson took his mother’s maxim “that the law affords no remedy for such outrages that can satisfy the feelings of a true man” to heart, and involved himself in more than 13 “affairs of honor.” These showdowns left his body so filled with lead that people said he “rattled like a bag of marbles.”

Practice Stoic Self-Discipline

Jackson’s anger, born from his troubled youth, constantly threatened his ability to reach his goals. He knew he had to get it under control if he wished to find success. He was never able to entirely subdue his temper, but he was largely able to transform himself from reckless hothead to cool and calculating leader.

During his presidential campaigns, his opponents were constantly trying to provoke Jackson, goading him to lose control and reveal himself as exactly what some voters feared him to be: a knuckle-dragging, unhinged frontiersmen, unfit for the highest office in the land. Though they besmirched the character of his wife, Jackson’s great Achilles’ heel, he would not give them the satisfaction of an embarrassing outburst.

The election of 1824 was a particularly bitter contest. Jackson had won the popular vote, but without a majority from the electoral college, the decision was thrown to the House, which chose John Quincy Adams to be the next president. On the night he lost the election, Jackson attended a party at the White House where he came face-to-face with Adams. The moment was tense as the two men stared at one another. With his wife on his arm, it was Jackson who made the first move, extending his hand to the president-elect and cheerfully inquiring, “How do you do, Mr. Adams? I give you my left hand, for the right, as you see, is devoted to the fair. I hope you are very well, sir.” Answering with what an eyewitness recalled as “chilling coldness” Adams responded: “Very well, sir; I hope General Jackson is well.” A party guest was struck by the irony of the exchange: “It was curious to see the western planter, the Indian fighter, the stern soldier, who had written his country’s glory in the blood of the enemy at New Orleans, genial and gracious in the midst of a court, while the old courtier and diplomat was stiff, rigid, cold as a statue!”

Be a Badass

Andrew Jackson was the first president on which an assassination attempt was made. And he is the only one who gave his would-be assassin a thorough thumping.

In 1835, Jackson was leaving a funeral when a deranged man, Richard Lawrence, approached the president wielding two pistols. Lawrence leveled one of his guns and pulled the trigger. It failed to fire. He pointed at Jackson with the other pistol, but it misfired as well. Without blinking, the 68-year-old president went after Lawrence with his cane, striking him several times before others in the crowd subdued the would-be assassin.

But Jackson’s greatest claim to badass status actually came years earlier. In 1806, in a dispute over a horse race and an insult made about his wife, Charles Dickinson challenged Jackson to a duel. Dickinson was a well-known sharpshooter and Jackson felt his only chance to kill him would be to allow himself enough time to take an accurate shot. So as the two faced off along the banks of the Red River in Kentucky, Jackson purposely allowed Dickinson to shoot him first. He hardly quivered as the bullet lodged in his ribs. Jackson then calmly leveled his pistol, took aim, and knocked Dickinson off. It was only then that he took heed of the fact that blood was dripping into his boot. Dickinson’s musket ball was too close to his heart to be removed and forever remained lodged in Jackson’s chest. The wound would lend him a perpetual hacking cough, cause him persistent pain, and compound the many health problems that would beleaguer him throughout life.

Yet Jackson never regretted the decision, saying, “If he had shot me through the brain, sir, I should still have killed him.”

__________

Sources:

American Lion by Jon Meacham

Andrew Jackson by James Curtis